Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig

26./27. 1. und 1. 2. 2012

Konvergenzerscheinungen bei der karnivoren

Philcoxia minensis 1 – ein weiteres Problem für die Synthetische Evolutionstheorie

"Next relatives to the […] genus Philcoxia are found in Gratioleae, as previously suggested. Without any doubt, Gratioleae have no close connection to Lentibulariaceae, despite some morphological similarity. Should further tests identify Philcoxia as a truly carnivorous plant 2 , this would be the third independent origin of the syndrome within the order.

Schäferhoff, Fleischmann, Fischer, Albach, Borsch, Heubl, Müller (2010) 3

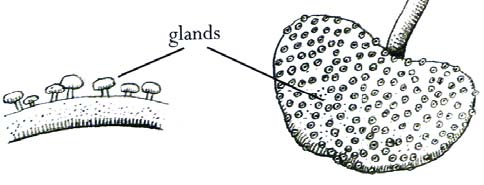

KONVERGENZEN: Klebfalle (flypaper trap/adhesive leaves displaying (a) stalked capital glands producing (b) sticky substances (c) on the upper leaf surfaces, (d) luring, (e) capturing, (f) digesting prey (nematodes and other soil organisms), (g) showing phosphatase activity (h) on the surface of the glandular trichomes, (i) absorbing the prey’s nutrients (j) metabolizing the animal proteins into Philcoxia species specific proteins). 4

Quelle: http://imageshack.us/photo/my-images/225/philcoxiaminensisfritscug9.png/

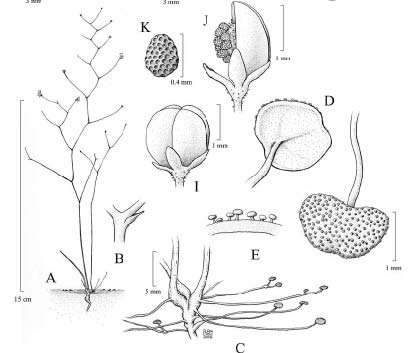

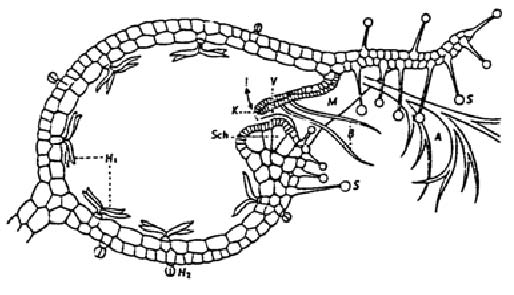

Abb. 1. A: Habitus von Philcoxia minensis. B: Hochblatt an der Infloreszenz. C: Ansatz der nach oben strebenden Blätter am etwas geschwollenen Stamm. D: Blatt von unten und rechts daneben die Blattoberseite mit den zahlreichen stalked capital glands . E: Querschnitt durch die Lamina. I: Samenkapsel. K: Samen. J: Teilweise geöffnete Samenkapsel mit Samenkörnern. Abbildungen nach Fritch et al. (2007) jedoch ohne H, F und G, die Blütenstrukturen darstellen (auch von Pereira and Oliveira in McPherson 2010, p. 1095 wiedergegeben, dort aber A verändert und B weggelassen).

Quelle: http://www.wissenschaft-online.de/sixcms/media.php/912/thumbnails/0109planze0.jpg.1147629.jpg

Abb. 2. Aus Pereira et al. (2012) gemäß zitierter Internetadresse: A: Erscheinungsbild von Philcoxia minensis in ihrer natürlichen Umgebung (Serra do Cabral, Minas Gerais, Brasilien). B: Ausgegrabene Pflanze: zeigt die nach oben strebenden 0,5 bis 1,5 mm kleinen Blätter. C: Zwei von Sandkörnern bedeckte Blätter. D: Mehrere Blätter; hier wurde nach Pereira et al. der Sand weggeblasen. E: Einzelne Blüte.

Kaum eine Thematik hat dem mit zufälliger Mutation und Selektion arbeitenden Neodarwinismus 5 (=Synthetische Evolutionstheorie) mehr Schwierigkeiten bereitet als die Konvergenzfrage 6 :

Convergence is a deeply intriguing mystery, given how complex some of the structures are. Some scientists are skeptical that an undirected process like natural selection and mutation would have stumbled upon the same complex structure many different times (Meyer et al. 2007, p. 48).

Nun stellt gerade das Phänomen der Konvergenz den Neodarwinismus vor weitere große Probleme. Denn wenn schon die einmalige Entstehung vollkommen "angepasster" Organe oder Merkmale durch Auslese zufälliger Mutationen kaum erklärbar ist, so entzieht sich die mehrfache Ausbildung gleichartiger Organe noch weiter der neodarwinistischen Interpretation (Kahle 1998, p. 99, zu weiteren Schwierigkeiten siehe z. B. Luskin 2010 7 , J. M. 2011 8 ).

Ein Evolutionsbiologe wie S. C. Morris (Universität Cambridge), der das Konvergenzthema ausführlich diskutiert hat, machte die folgende Beobachtung zur Wortwahl in der biologischen Literatur (2003, pp. 127/128):

During my time in the libraries I have been particularly struck by the adjectives that accompany descriptions of evolutionary convergence. Words like, 'remarkable', 'striking', 'extraordinary', or even 'astonishing' and 'uncanny' are commonplace [...] the frequency of adjectival surprise associated with descriptions of convergence suggests to me there is almost a feeling of unease in these similarities. Indeed, I strongly suspect that some of these biologists sense the ghost of teleology looking over their shoulders. 9

Zu Konvergenzerscheinungen bei den karnivoren Pflanzen haben wir (Lönnig und Becker 2004, p. 5) angemerkt:

[M]ost writers agree that the nine fully substantiated families belonging to six different plant orders 10 already clearly show that carnivory in plants must have arisen several times independently of each other. In a scenario of strong convergence based on morphological data the pitchers might have arisen seven times separately, adhesive traps at least four times, snap traps two times and suction traps possibly also two times. Nevertheless, such conclusions have been questioned by some authors as perhaps 'more apparent than real' (Juniper et al., 1989, pp. 4, 283), discussing the origin of all carnivorous plant families from one basic carnivorous stem group (Croizat had already dedicated a larger work to this hypothesis in 1960). The independent origin of complex synorganized structures, which are often anatomically and physiologically very similar to each other, appears to be intrinsically unlikely to many authors so that they have tried to avoid the hypothesis of convergence as far as possible. Yet, molecular comparisons have corroborated the independent origin of at least five of the carnivorous plant groups. However, Dionaea and Aldrovanda, which according to most morphological investigations were thought to have arisen convergently, are now placed very near each other 'and this pair is sister to Drosera' (Cameron et al., 2002, p. 1503). 11

Die Gattung Philcoxia liefert uns neuerdings ein weiteres Beispiel für eine komplex-synorganisierte Konvergenzerscheinung bei den Karnivoren (Pereira et al. 2012 12 ).

Hier zunächst ein paar Auszüge aus Pressemitteilungen und Kommentaren zur Bestätigung der Karnivorie aus der populärwissenschaftlichen Literatur.

Frankfurter Rundschau vom 9. 1. 2012 13 :

Forscher haben einen völlig neuen Typ von fleischfressenden Pflanzen entdeckt: Die in Brasilien wachsende Philcoxia minensis nutzt winzige klebrige Blätter, um im Boden lebende Fadenwürmer zu fangen und zu verdauen. Diese Fangstrategie sei einzigartig. Man kenne keine andere fleischfressende Pflanzenart, die ihre Blätter als unterirdische Klebfallen einsetze 14 , berichtet ein internationales Forscherteam im Fachmagazin "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences".

"…Das auffallendste Merkmal ist…, dass die Pflanze zahlreiche ihrer nur 0,5 bis 1,5 Millimeter kleinen Blätter unter die Oberfläche des Sandbodens absenkt" 15 , schreiben Caio Pereira von der Universidade Estadual de Campinas in Brasilien und seine Kollegen. Auf den winzigen Blättern sitzen zahlreiche Drüsen, die die Oberfläche klebrig machen. Bei näherer Betrachtung entdeckten die Wissenschaftler auf den Blättern zahlreiche anklebende Sandkörner, aber auch tote, weniger als einen Millimeter lange Fadenwürmer. Das habe bei ihnen den Verdacht geweckt, dass Philcoxia fleischfressend sein könnte und sich von diesen Fadenwürmern ernähre, sagen die Forscher."

Die Blätter befinden sich jedoch in der lichtdurchfluteten oberen Schicht des weißlich erscheinenden Quarzsandes. Die Fotosynthese ist damit weiter gewährleistet.

Deutschlandradio 11. 1. 2012 16 :

Im hellen Quarzsand bekommen die Blätter zwar immer noch genügend Licht, um Fotosynthese zu betreiben, aber diese seltsame Bauweise musste trotzdem einen guten Grund haben. Oliveira sammelte Indizien. "Zuerst einmal haben wir gesehen, dass die Blätter auf ihrer Oberfläche viele Drüsen tragen, die eine klebrige Substanz absondern. Und wir beobachteten, dass es um die Blätter herum auffällig viele Fadenwürmer gab. Diese beiden Beobachtungen zusammen brachten uns auf die Idee, dass Philcoxia eine fleischfressende Pflanze sein könnte."

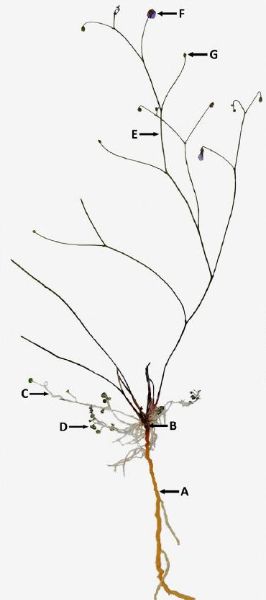

Abb. 3. Ganze Pflanze verkleinert (ebenfalls aus Pereira et al. 2012). Die kleinen 0,5 bis 1,5 Millimeter kleinen zur lichtdurchfluteten Oberfläche des Quarzsandes strebenden Blätter sind wieder gut zu erkennen. A: Wurzelsystem. B: Kurzer aufrechter Stengel. C: Lateraler ’stem’/Petiolus. D: Blattspreite. E: Zweig des Blütenstandes. F: Blüte. G: Frucht.

Spiegel Online Wissenschaft vom 10. 1. 2012 schreibt u. a. 17 :

Um herauszufinden, ob Philcoxia minensis Nährstoffe aus Beutetierchen aufnimmt, markierte das Team zunächst Fadenwürmer mit Stickstoff 15, einem Isotop des Gases 18 , das häufig bei solchen Versuchen verwendet wird. Anschließend brachten sie die Würmer in das Erdreich nahe der Pflanze.

Tatsächlich enthielten neu gewachsene Blätter den Forschern zufolge später größere Mengen Stickstoff 15. Das zeige, dass die Pflanzen die Würmer verdaut hätten, erklärt Biologe Rafael S. Oliveira.

Bild der Wissenschaft vom 9. 1. 2012 19 :

Offenbar nutzt Philcoxia minensis zur Verdauung ihrer Opfer auch ein Enzymsystem, das bereits von anderen fleischfressenden Pflanzen bekannt ist, zeigten weitere Untersuchungen der Forscher. Sie konnten die Aktivität eines Biokatalysators namens Phosphatase auf der Blattoberfläche der unterirdischen Fangblättchen nachweisen. Mit diesem Enzym zerlegen viele bekannte Carnivoren ihre tierische Kost in nutzbare Nährstoffeinheiten. Der Nachweis von Phosphatase dokumentiert den Wissenschaftlern zufolge, dass auch Philcoxia minensis aktiv verdaut und nicht nur Nährstoffe aufnimmt, die durch den Abbau der toten Würmer von Mikroben freigesetzt werden.

Soweit einige Stimmen aus der Presse und Populärwissenschaft.

Sehen wir uns jetzt einmal die Blätter etwas näher an. Pereira and Oliveira, die sich auf Philcoxia spezialisiert haben, bemerken zu den Blättern in McPhersons Riesenarbeit Carnivorous Plants and their Habitats, "[they] develop underground and grow to surface level” (2010, pp. 1094/1097):

All three species [of Philcoxia] are characterised by short subterranean stems that are sparsely and irregularly branched, and bear leaves that develop underground and grow to surface level through the substrate on long, narrow petioles. The lamina of the foliage is peltate, circular or reniform, and positioned at, or immediately below, ground level. 20 The upper surface of the foliage is lined with uniform stalked capitate glands that are between 0.1 – 0.5 mm tall and bear secreted droplets of a sticky mucilage [darauf Hinweis auf die dazugehörenden Abb.].

Das ist ein wichtiger Punkt: Sie senken also ihre Blätter nicht abwärts, sondern streben nach unterirdischem Beginn der Entwicklung aufwärts ("grow to the surface level" ganz im Gegensatz zu den Fallen Genliseas und meist auch Utricularias).

Und weiter auf den Seiten 1099/1100 zu den Themen Habitats and Ecology erfahren wir weitere Gründe, warum sich die Blätter unterirdisch entwickeln:

Exposed to hot and extremely bright conditions, the foliage of Philcoxia usually develop below surface level, often below the sand crust, and is covered with a thin layer of sand grains. The covering of sand potentially protects the foliage from desiccating heat, and allows the leaves to develop in slightly moister conditions where microscopic prey (especially nematodes) are more abundant. The sand atop of the foliage is translucent and so allows diffused light to reach the surface of the leaves, but prevents over-exposure, especially by ultra violet light. The exudates released by the minute stalked glands affix individual grains of sand to the surface of the foliage, but their primary function may enable carnivory or mobilisation of phospates in the soil.

Und zu seiner Abbildung 630, p. 1101 (hier nicht wiedergegeben), bemerkt er: "This environment is exposed to extreme temperature and moisture fluctuation. The reflectivity of the quartzitic sand ensures that light levels are extremely high."

http://www.plante-carnivore.fr/philcoxia-des-plantes-carnivores-meconnues/

Abb. 4. Blätter von Philcoxia minensis. Sand weggeblasen (photo by Pereira and Oliveira in Stewart McPherson 2010, p. 1089). Man findet sie – gemäß obigem Zitat – gewöhnlich "at, or immediately below, ground level” (also auch "at") oder mit Fritsch et al. (2007, p. 453) "lamina subterranian or (when mature) at soil surface”.

Barry Rice bemerkt zur behaupteten Entdeckung eines "völlig neuen Typs von fleischfressenden Pflanzen" (2012: http://www.sarracenia.com/faq/faq5435.html ), eine Behauptung, die auch von Pereira et al. (2012) proklamiert worden ist:

This is – so far – the only carnivorous plant that seems to specialize in nematodes – although nematodes have been observed being killed and eaten by other carnivorous plants. Also, it has been noted that this is the only sticky-leaved carnivorous plant that hunts under the sand. However, I'd like to point out that Drosera zonaria is often partly or completely buried in the sand.

Quelle: http://www.flickr.com/photos/fotosynthesys/5305883080/ Abb. 5. Bei der australischen Drosera zonaria sind die Fangblätter oft ebenfalls "partly or completely buried in the sand". (Das sieht übrigens ebenfalls ganz nach Quarzsand aus.)

Zum oft zitierten Vergleich von Philcoxia mit Utricularia bemerken Pereira and Oliveira (in McPherson 2010, p. 1090):

Although superficially resembling terrestrial Utricularia, Philcoxia are distinguished by their subterranean stems and presence of roots, five-lobed calyces and a different flower structure, and peltate leaves that develop at or below the surface.

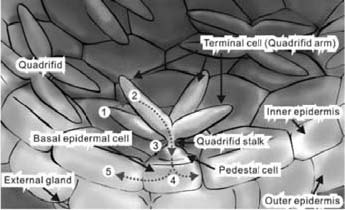

Und zu ergänzen wäre die völlig unterschiedliche Fallenstruktur: Klebfalle bei Philcoxia im deutlichen, multikomponenten Unterschied zur wesentlich komplexeren Saugfalle von Utricularia, einschließlich des Aufbaus und der Funktion der Drüsen.

Quellen: http://www.dradio.de/dlf/sendungen/forschak/1649940/bilder/image_main/ und http://ejournal.sinica.edu.tw/bbas/content/2011/1/Bot521-06/Bot521-06-8.jpg

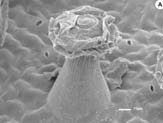

Abb. 6. Links: Die Sekretdrüsen von Philcoxia minensis unter dem Elektronenmikroskop (Bild: PNAS/Pereira et al. 2012).

Sie unterscheiden sich deutlich von den Drüsen Utricularias (rechts) sowohl in der Form als auch in der Funktion (Bild aus Juang et al. 2011).

Zur Unwahrscheinlichkeit der Konvergenzerscheinungen bei Philcoxia durch definitionsgemäß

ungerichtete Zufallsmutationen und Selektion.

Hier seien zunächst die prinzipiellen Hauptpunkte zur Unwahrscheinlichkeit der neodarwinistischen Erklärung komplexer Konvergenzerscheinungen im Tier- und Pflanzenreich nach Meyer et al. (2007) und Kahle (1998) wegen ihrer grundlegenden Bedeutung kurz wiederholt mit der Bitte an den Leser, sich diese Problematik für den Neodarwinismus tief einzuprägen und möglichst bewusst zu machen, und zwar in Verbindung mit den auf der nächsten Seite aufgeführten Einwänden zum Thema Co-option (availability, synchronization, localization, coordination and interface compatibility):

Some scientists are skeptical that an undirected process like natural selection and mutation would have stumbled upon the same complex structure many different times (Meyer et al. 2007, p. 48).

[W]enn schon die einmalige Entstehung vollkommen "angepasster" Organe oder Merkmale durch Auslese zufälliger Mutationen kaum erklärbar ist, so entzieht sich die mehrfache Ausbildung gleichartiger Organe noch weiter der neodarwinistischen Interpretation (Kahle 1998, p. 99, zu weiteren Schwierigkeiten siehe z. B. Luskin 2010 21 , J. M. 2011 und weitere Autore mit vielen Beispielen 22 ).

Zu den Konvergenzerscheinungen bei Philcoxia im Vergleich zu anderen unabhängig von dieser Gattung entstandenen karnivoren Pflanzen (wie Drosera, Drosophyllum 23 , Byblis, Pinguicula, Roridula), wurden oben folgende Punkte aufgeführt:

Klebfalle (flypaper trap/adhesive leaves displaying (a) stalked capital glands producing (b) sticky substances (c) on the upper leaf surfaces, (d) luring, (e) capturing, (f) digesting prey (nematodes and other soil organisms), (g) showing phosphatase activity (h) on the surface of the glandular trichomes, (i) absorbing the prey’s nutrients (j) metabolizing the animal proteins into Philcoxia species specific proteins). 24

Selbstverständlich soll nach der herrschenden Evolutionstheorie die Entwicklung der Karnivorie bei Philcoxia nicht beim Punkt Null beginnen. Die Punkte (a) bis (c) werden vielmehr allgemein für die weitere Entwicklung als gegeben vorausgesetzt. Dass damit deren Existenz noch nicht erklärt ist und welche genetischen Systeme und welche tiefgreifenden Probleme für den Neodarwinismus damit verbunden sind, wurde von mir kürzlich schon näher diskutiert (Lönnig 2010/2012, pp. 167/168) (siehe auch http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ) und als Buch die 3. Auflage 2012 25 .

Selbst unter der Voraussetzung, dass auch die meisten der übrigen Strukturen und Funktionen zur Karnivorie bei Philcoxia nicht völlig ohne eine "präadaptive" Grundlage im Pflanzenreich (allgemein) sind 26 , so wird doch – allein schon aufgrund der Tatsache, dass eine mutationsgenetische Umwandlung einer nichtkarnivoren Pflanze in eine karnivore 27 auch in Milliarden und Abermilliarden von induzierten Mutationsereignissen niemals gelungen ist 28 , der vorurteilsfreie Leser unmittelbar verstehen, dass in der detaillierten Ausgestaltung (a) morphologischer, (b) anatomischer, (c) physiologischer und entsprechend (d) genetischer Strukturen zum präzis synorganisierten konvergent entstandenen Karnivorensyndrom für den Neodarwinismus ein schweres Problem steckt (insbesondere die Feinabstimmung).

Ist Co-option (Exaptation) die Lösung?

Co-option (exaptation) ist neuerdings (wieder) das Zauberwort, mit dem offenbar viele Evolutionstheoretiker glauben, das Synorganisationsproblem grundsätzlich gelöst zu haben.

Unter einer Exaptation wird in der Evolutionsbiologie die Nutzbarmachung einer Eigenschaft für eine Funktion verstanden, für die sie ursprünglich nicht entstanden war – mit anderen Worten: Es handelt sich um eine "kreative" Zweckentfremdung. ( http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exaptation ) [Oder in der englischen Fassung:] Exaptation, cooption, and preadaptation are related terms referring to shifts in the function of a trait during evolution . For example, a trait can evolve because it served one particular function, but subsequently it may come to serve another. ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exaptation )

Ich habe die Thematik in der Karnivorenarbeit schon wiederholt angesprochen (Lönnig 2012, pp. 37, 95, 99, 192, 109; siehe auch http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ).

Angus Menuge hat die folgenden Bedingungen für Co-option am Beispiel des bacterial flagellum (2004, p. 104-111) herausgearbeitet und es bietet sich an, die Hauptpunkte auch auf das Karnivorensyndrom anzuwenden. Er schreibt (pp. 104/105):

For a working flagellum to be built by exaptation, the five following conditions would all have to be met:

C1: Availability. Among the parts available for recruitment to form the flagellum, there would need to be ones capable of performing the highly specialized tasks of paddle, rotor, and motor, [and applied to Philcoxia, to repeat: (a) stalked capital glands producing (b) sticky substances (c) on the upper leaf surfaces, (d) luring, (e) capturing, (f) digesting prey, (g) showing phosphatase activity (h) on the surface of the glandular trichomes (i) absorbing the prey’s nutrients (j) metabolizing the animal proteins into Philcoxia species specific proteins] even though all of these items serve some other function or no function.

C2: Synchronization. The availability of these parts would have to be synchronized so that at some point, either individually or in combination, they are all available at the same time.

C3: Localization. The selected parts must all be made available at the same "construction site", perhaps not simultaneously but certainly at the time they are needed.

C4: Coordination. The parts must be coordinated in just the right way: even if all of the parts of a flagellum [or all the parts of a complex trap of a carnivorous plant] are available at the right time, it is clear that the majority of ways of assembling them will be non-functional or irrelevant.

C5: Interface compatibility. The parts must be mutually compatible, that is, "well-matched" and capable of properly "interacting": even if a paddle, rotor, and motor [or the parts mentioned above for a trap of a carnivorous plant] are put together in the right order, they also need to interface correctly.

Availability – zumeist der einzige Punkt der in evolutionstheoretischen Abhand-lungen zu diesen Fragen berücksichtigt wird (vgl. Fußnote 164, p. 98 in http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ) – reicht definitiv nicht aus, um die Entstehung eines Karnivorensyndroms zu erklären. Kitano bemerkte zum Thema Systems Biology: A Brief Overview (2002, zitiert nach Luskin 2007):

Identifying all the genes and proteins in an organism [and all the anatomical structures and functions of the trap of a carnivorous plant] is like listing all the parts in an airplane. While such a list provides a catalog of the individual components, by itself it is not sufficient to understand the complexity underlying the engineered object. We need to know how these parts are assembled to form the structure of the airplane.

"In any case, the co-option argument tacitly presupposes the need for the very thing it seeks to explain – a functionally interdependent system of proteins" (Minnich und Meyer 2004). Dembski und Witt (2010, p. 54) beantworten die Frage: "What is the one thing in our experience that co-opts irreducibly complex machines and uses their parts to build a new and more intricate machine?" – wie folgt: "Intelligent agents."

Um jedoch die sich multiplizierenden Unwahrscheinlichkeiten – zumal bei den mehrfach konvergent entstandenen Fangapparaten der Karnivoren – durch Mutation und Selektion in konkreten Zahlen (zumindest Näherungszahlen) aufzuzeigen, die etwa in den oben aufgeführten Punkten (d) bis (j) stecken, bedarf es der weiteren Forschung bei Philcoxia, die im Folgenden kurz umrissen sei:

Forschungsaufgaben zu Philcoxia:

Sind völlig neue Gene involviert? Wieviele veränderte Gensequenzen und Genfunktionen (Regulator- und Targetgene) sind bei Philcoxia für die Karnivorie zuständig im Vergleich zu nächstverwandten nichtkarnivoren Gattungen? Inwieweit sind die DNA-Sequenzen verändert? (Zahl der Substitutionen, Indels etc.) (Vgl. weiter zur Co-option-Problematik auf der genetischen Ebene, peer-reviewed und in den Kernfragen bis heute (2012) topaktuell, Kunze et al. 1997, zitiert unten pp. 16/17.) Überdies gibt es zur Karnivorie von Philcoxia noch offene Fragen zu den anatomischen und physiologischen Funktionen: Sind außer den Phosphatasen noch weitere Enzyme an der Verdauung beteiligt? Wie genau funktioniert die nutrient absorption? Sind die stalked capitate glands daran beteiligt? Woraus bestehen die sticky substances? Die Hinweise auf active attraction sind mit biologischen Daten zu konkretisieren. Welche soil organisms außer den Nematoden werden sonst noch gefangen und verdaut? Wie tief gehen die Konvergenzerscheinungen im Vergleich zu den anderen, unabhängig von Philcoxia entstandenen Klebfallen anatomisch, physiologisch und genetisch – etwa bei Gattungen wie Drosera, Drosophyllum 29 , Byblis, Pinguicula, Roridula? 30 Wie mit Conway Morris oben zitiert und von Luskin weiter dokumentiert, wurden die zahlreichen Konvergenzen im Tier- und Pflanzenreich oft mit großem Erstaunen zur Kenntnis genommen (zu den karnivoren Pflanzen siehe das längere Zitat nach Lönnig und Becker oben p. 3). Konvergenzen in dieser häufig spezifisch-übereinstimmenden Form waren demnach für den Neodarwinismus völlig unerwartet und entsprechend auch nicht vorausgesagt worden.

Wie steht es mit intelligentem Design (ID)?

Casey Luskin schreibt zu den Erwartungen und Voraussagen von ID (2005 und 2011 – das Thema ID wurde ja oben mit dem Zitat nach Dembski und Witt schon kurz angesprochen):

"Convergence will occur routinely. That is, genes and other functional parts will be re-used in different and unrelated organisms.” 31

Auf der folgenden Seite seien noch einmal 32 seine drei informativen Tabellen zum Thema A Positive, Testable Case for Intelligent Design wiedergegeben (aus Luskin 2005/2011) 33 – die für unsere Fragestellung relevanten Schlüsselpunkte zum Konvergenzthema wurden von mir hervorgehoben (zur Literatur siehe Luskin):

Table 1. Ways Designers Act When Designing (Observations):

(1) Intelligent agents think with an "end goal" in mind, allowing them to solve complex problems by taking many parts and arranging them in intricate patterns that perform a specific function (e.g. complex and specified information): "Agents can arrange matter with distant goals in mind. In their use of language, they routinely 'find' highly isolated and improbable functional sequences amid vast spaces of combinatorial possibilities." (Meyer, 2004 a) "[W]e have repeated experience of rational and conscious agents – in particular ourselves – generating or causing increases in complex specified information, both in the form of sequence-specific lines of code and in the form of hierarchically arranged systems of parts. ... Our experience-based knowledge of information-flow confirms that systems with large amounts of specified complexity (especially codes and languages) invariably originate from an intelligent source from a mind or personal agent." (Meyer, 2004 b.)

(2) Intelligent agents can rapidly infuse large amounts of information into systems: "Intelligent design provides a sufficient causal explanation for the origin of large amounts of information, since we have considerable experience of intelligent agents generating informational configurations of matter." (Meyer, 2003.) [See also Lönnig 2000/2001.] "We know from experience that intelligent agents often conceive of plans prior to the material instantiation of the systems that conform to the plans – that is, the intelligent design of a blueprint often precedes the assembly of parts in accord with a blueprint or preconceived design plan." (Meyer, 2003.)

(3) Intelligent agents re-use functional components that work over and over in different systems (e.g., wheels for cars and airplanes): "An intelligent cause may reuse or redeploy the same module in different systems, without there necessarily being any material or physical connection between those systems. Even more simply, intelligent causes can generate identical patterns independently." (Nelson and Wells, 2003.)

(4) Intelligent agents typically create functional things (although we may sometimes think something is functionless, not realizing its true function): "Since non-coding regions do not produce proteins, Darwinian biologists have been dismissing them for decades as random evolutionary noise or 'junk DNA.' From an ID perspective, however, it is extremely unlikely that an organism would expend its resources on preserving and transmitting so much 'junk.'" (Wells, 2004.)

These observations can then be converted into hypotheses and predictions about what we should find if an object was designed. This makes intelligent design a scientific theory capable of generating testable predictions, as seen in Table 2 below:

Table 2. Predictions of Design (Hypothesis):

(1) Natural structures will be found that contain many parts arranged in intricate patterns that perform a specific function (e.g. complex and specified information).

(2) Forms containing large amounts of novel information will appear in the fossil record suddenly and without similar precursors.

(3) Convergence will occur routinely. That is, genes and other functional parts will be re-used in different and unrelated organisms.

(4) Much so-called "junk DNA" will turn out to perform valuable functions.

These predictions can then be put to the test by observing the scientific data, leading to conclusions:

Table 3. Examining the Evidence (Experiment and Conclusion):

(1) Language-based codes can be revealed by seeking to understand the workings of genetics and inheritance. High levels of specified complexity and irreducibly complexity are detected in biological systems through theoretical analysis, computer simulations and calculations (Behe & Snoke, 2004; Dembski 1998b; Axe et al. 2008; Axe, 2010a; Axe, 2010b; Dembski and Marks 2009a; Dembski and Marks 2009b; Ewert et al. 2009; Ewert et al. 2010; Chiu et al. 2002; Durston et al. 2007; Abel and Trevors, 2006; Voie 2006), "reverse engineering" (e.g. knockout experiments) (Minnich and Meyer, 2004; McIntosh 2009a; McIntosh 2009b) or mutational sensitivity tests (Axe, 2000; Axe, 2004; Gauger et al. 2010). [In his 2005 paper C. L. mentions the bacterial flagellum, the specified complexity of protein bonds and the simplest self-reproducing cell.]

(2) The fossil record shows that species often appear abruptly without similar precursors. (Meyer, 2004; Lönnig, 2004; McIntosh 2009b.)

(3) Similar parts are commonly found in widely different organisms. Many genes and functional parts not distributed in a manner predicted by ancestry, and are often found in clearly unrelated organisms. (Davison, 2005; Nelson & Wells, 2003; Lönnig, 2004; Sherman 2007.)

(4) There have been numerous discoveries of functionality for "junk-DNA." Examples include recently discovered surprised functionality in some pseudogenes, microRNAs, introns, LINE and ALU elements. (Sternberg, 2002, Sternberg and Shapiro, 2005; McIntosh, 2009a.)

Fazit: Die karnivoren Pflanzen mit ihren zahlreichen Konvergenzerscheinungen sind ausgezeichnete Kandidaten für ID.

Einige potentielle Missverständnisse zu Philcoxia

a) Philcoxia gehört zu den Wegerichgewächsen (Plantaginaceae). Die Gattung Wegerich (Plantago) bildet manchmal schlauchförmige Blätter (Barthlott et al. 2004, p. 58 und viele weitere Autoren), die häufig als ein erster oder wichtiger Schritt zu vermuteten nahe verwandten schlauchförmigen Karnivoren gedeutet werden (vgl. dagegen Lönnig 2010/2012, pp. 91-93, 130). Schäferhoff et al. 2010, p. 4

34

haben die neueren Befunde zu den Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen bei den Lamiales nach evolutionären Voraussetzungen wie folgt zusammengefasst (Hervorhebungen im Schriftbild wieder von mir; siehe auch schon oben z. T. die Fußnote 3).

The most prominent case for a family that turned out to be polyphyletic are the Scrophulariaceae. In their traditional circumscription they used to be the largest family (more than 5000 spp. [ 44 ]) among Lamiales. In the first report on the polyphyly of Scrophulariaceae [ 45 ], members of the "old" Scrophulariaceae sensu lato were found in two different clades, named "scroph I" (including Scrophularia) and "scroph II" (containing Plantago, Antirrhinum, Digitalis, Veronica, Hippuris and Callitriche). The first clade was later [ 38 ] referred to as Scrophulariaceae sensu stricto (s. str.), while the "scroph II" clade was called Veronicaceae. However, since Plantago is contained in that clade, Plantaginaceae as the older name should be given priority and meanwhile became accepted for this clade [ 46 , 28 ]. Plantaginaceae experienced an enormous inflation since these early studies, when more and more genera from former Scrophulariaceae s. l. were included in phylogenetic studies and identified as members of this newly circumscribed family [ 22 , 37 - 39 ]. Some genera from tribe Gratioleae, including Gratiola itself, have been found in a well supported clade. Based on the unknown relationships to the other lamialean families, it has been suggested to separate this part of the inflated Plantaginaceae by restoring family rank to former tribe Gratioleae from Scrophulariaceae as traditionally circumscribed [ 2 ].

Die manchmal zu beobachtenden schlauchförmigen Blätter bei Plantago haben weder etwas mit der Karnivorie an sich und schon gar nicht mit der von Philcoxia zu tun. Plantago und Philcoxia gehören außerdem zu unterschiedlichen Familien: Plantaginaceae und Gratiolaceae.

- b) Missverständnis: Philcoxia bestätigt die Hypothese von Barthlott et al. (2004, p. 60): "Durch Herabsenken der Fangblätter [von Pinguicula] ins Erdreich kann man sich die Entstehung der Genlisea-Reusenfallen und Utricularia-Fangblasen vorstellen." 35

Um es zu wiederholen: Die Fangblätter von Philcoxia werden nicht ins Erdreich herabgesenkt, sondern streben nach unterirdischem Beginn der Entwicklung aufwärts ("grow to the surface level" ganz im Gegensatz zu den Fallen Genliseas und meist auch Utricularias). Sie befinden sich dann in der lichtdurchfluteten oberen Schicht des weißlich erscheinenden Quarzsandes, womit die Fotosynthese weiter gewährleistet ist. Pereira and Oliveira haben für diese Anpassungserscheinung die speziellen ökologischen Bedingungen sehr gut herausgearbeitet (siehe die Details oben p. 5). Die Genlisea-Reusenfallen "extend downwards from the rosette, growing through the soil. These carnivorous leaves do not photosynthesize as they lack chlorophyll and are underground, and consequently appear whitish or translucent (Figures 635 and 636)" (Fleischmann 2010, p. 1112 in McPherson). Auch die Utricularia-Fangblasen der terrestrischen Arten streben generell nicht zum Licht; vielmehr deutlich abwärts (also positiv geotrop/positiv gravitrop 36 oder negativ fototrop 37 ) bei den sogenannt "primitivsten" Arten U. multifida (Polypompholyx), U. tenella, U. westonii. Die Fangorgane von Philcoxia wachsen jedoch negativ geotrop (negativ gravitrop oder positiv fototrop) – was recht ungewöhnlich ist, denn "viele Seitenzweige und Blätter, ebenso Erdsprosse, reagieren diagravitrop [wachsen meist horizontal] oder plagiogravitrop [in einem bestimmten Winkel schräg abwärts]" (Strasburger).

"Immerhin" könnte man vielleicht noch einwenden, "liegen die Fangorgane von Philcoxia oft unter der Erdbodenoberfläche" ("at, or immediately below, ground level" oder "lamina subterranian or (when mature) at soil surface"). Die Gründe (wie zitiert): Sie wächst unter extrem heißen und hellen Bedingungen. Die dünne Sandschicht schützt die Blätter vor Austrocknung und unter diesen geringfügig feuchteren Bedingungen sind Nematoden häufiger (auch mobilisation of phosphates in the soil). Der Quarzsand ist lichtdurchlässig, aber verhindert die übermäßige Einstrahlung von ultraviolettem Licht.

Mir ist bisher jedoch nicht bekannt, dass man die generell an extrem feuchte Standorte gebundenen Arten der Gattungen Genlisea und Utricularia von solchen speziellen "Wüstenpflanzen" ableitet (vgl. Lönnig 2010/2012, pp. 119-124). Weiter besteht nicht der geringste Grund zur Annahme, dass sich die Blattorgane von Philcoxia oder die oben abgebildete Drosera zonaria jemals in Genlisea und Utricularia ähnliche Fallen-Strukturen umwandeln könnten. Die oft dünn mit Quarzsand bedeckten Fangblätter von Philcoxia und Drosera zonaria kann man in dieser Hinsicht (unter der Erdoberfläche) vielleicht als weitere Konvergenzerscheinungen sensu lato betrachten, wenn auch aus völlig anderen ökologischen Gründen mit deutlich unterschiedlichem Verhalten der gänzlich unterschiedlich strukturierten Fallen. (Zu Pinguicula siehe die Anmerkung p. 12.)

- c) Missverständnis: "Philcoxia ist ein Bindeglied zu Utricularia." Die direkte Gegenüberstellung der Klebfalle von Philcoxia – Saugfalle von Utricularia erübrigt wohl jede weitere Diskussion zu dieser unzutreffenden Behauptung:

Abb. 7. Links:Utricularia. "Längsschnitt durch die Blase. Schematisiert, zum Teil nach Lloyd. Klappe (zur Verdeutlichung) etwas angehoben gezeichnet; Gefäßbündel nicht gezeichnet. M Mündung bzw. Blaseneingang; K Verschlußklappe; V abdichtendes Velum; Sch Schwelle (Widerlager); B Borsten; A Antenne; H1 vierarmige Haare [Drüsen]; H2 Drüsenköpfchen." Aus Schmucker und Linnemann 1959.

Rechts: Philcoxia (siehe auch die Abbildung p. 1): Blattspreite mit kopfigen Drüsen. – Vgl. dazu weiter das Zitat p. 6 unten.

d) Missverständnis: Philcoxia ist die einzige Gattung, die in dieser speziellen Umgebung (Serra do Cabral, Minas Gerais, Brasilien) anzutreffen ist, da nur sie an diesen extremen Standorten durch ihre speziellen Anpassungen samt Karnivorie überleben kann (vgl. dazu die Behauptungen von Kutschera zu Utricularia vulgaris zitiert und kommentiert in http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf

pp. 136-139 und 152).

Pereira et al. (2012, pp. 1 und 4) haben Philcoxia mit acht weiteren Arten des Standorts verglichen ("…the dry-weight concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus in leaves of the species were significantly higher than that of the average among eight neighboring species [in Zahlenangaben])." "Comparative analyses were made for P. minensis (Plantaginaceae) and eight other flowering plant species, each from one of the following families: Clusiaceae, Cyperaceae, Ericaceae, Eriocaulaceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, Velloziaceae, and Xyridaceae." Die Autoren geben jedoch zu bedenken (p. 3) "…only a few plants such as sedges co-occur, suggesting a highly specialized niche." 38 Interessant wären noch genauere Angaben zur Frage, wie viele unterschiedliche Pflanzenspezies dort leben. 39

Alves et al. bemerken zu den Campos rupestres (2007):

The campos rupestres are a species-rich, extrazonal vegetation complex bound to Precambrian quartzite outcrops which emerge as a mosaic surrounded mostly by cerrado and caatinga. Campo rupestre outcrops and associated white sands occur on table mountains and ranges elevated above surrounding vegetation types (for instance the ranges of Espinhaço, Mantiqueira, Chapada Diamantina, and several isolated ranges in the state of Goiás), and more rarely also as rocky pans entirely level with surrounding cerrado (part of the Itutinga and Espinhaço ranges in Minas Gerais, etc.) [Siehe http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-33062007000300014 ]

In der unvollständigen Tabelle 1 (gemäß Herbarmaterial) werden allein 26 Pflanzenarten aus den unterschiedlichsten Familien für "D=Campos rupestres in south of the Espinhaco chain, Minas Gerais" aufgeführt. Aber selbst wenn an bestimmten Stellen nichts weiter als Philcoxia-Arten und "sedges" (Sauergrasgewächse; Cyperaceae) wachsen könnten (was jedoch den oben zitierten Vergleich mit den acht Arten infrage stellen würde), träfe das Wort von Karl von Goebel auch auf Philcoxia zu: "Es geht so, aber es geht auch anders." (Vgl. zur Selektionsfrage ausführlich weiter http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ) und als Buch, wie ebenfalls schon erwähnt die 3. Auflage 2012 40 . Zur "highly specialized niche" siehe die Anmerkung 2.

Anmerkung 1 (zu Pinguicula)

In http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf habe ich zu Pinguicula Folgendes geschrieben (p. 90):

Kommen wir nun zum Schritt (6) nach Barthlott et al.: "Durch Herabsenken der Fangblätter ins Erdreich kann man sich die Entstehung der Genlisea-Reusenfallen und Utricularia-Fangblasen vorstellen" (p. 60). Das erinnert mich wieder an den oben zitierten Leitgedanken nach Troll und Nägeli, dass sich die Deszendenztheoretiker "etwas ausdenken [vorstellen], was als möglich erscheint, um daraus ohne weiteres auf dessen Wirklichkeit zu schließen".

Ich habe jedoch mit dieser Vorstellung einige biologische Schwierigkeiten: Im Erdreich wird es mit der Fotosynthese bekanntlich etwas schwieriger als im hellen Sonnenlicht – und Pinguicula gehört generell zu den Lichtpflanzen (selbst die wenigen zu den tropisch-epiphytischen (Halb-)Schattenpflanzen gehörenden Pinguicula-Arten gedeihen nicht ohne Licht). Ja, im Boden gibt es Nematoden, Rotatorien und Ciliaten etc. (Was gibt es da sonst noch im Moorboden und in den anderen Böden? Vgl. p. 33) – aber nicht nur als Beutetiere, sondern auch als 'Schädlinge', für die die im Boden vermodernden Blätter das gefundene "Fressen" sein könnten. Ende der Weiterentwicklung! (Vgl. Versuch p. 222.)

Und auf p. 222 lesen wir:

Zu meinen Forschungsvorschlägen möchte ich hier kurz ergänzen, dass in einem Pilotversuch mit Pinguicula zur Untersuchung der Hypothese Barthlotts et al. ("Durch Herabsenken der Fangblätter ins Erdreich kann man sich die Entstehung der Genlisea-Reusenfallen und Utricularia-Fangblasen vorstellen") genau das eingetroffen ist, was von meiner Seite biologisch begründet prognostiziert wurde: Schon nach einigen Wochen war von den ins Erdreich herabgesenkten Fangblättern von Pinguicula praktisch nichts mehr übrig 41 (sogar zu meiner eigenen Überraschung, dass das derart schnell ging). "Ende der Weiterentwicklung!" (Vgl. p. 90 oben.)

In der Fußnote hatte ich u. a. weiter angemerkt, dass der (Pilot-) Versuch mit verschiedenen Pinguicula-Arten und unterschiedlichen Böden mit größeren Pflanzenzahlen erweitert werden müsste (wörtliche Wiedergabe siehe hier die Fußnote 41).

Gemäß den Beobachtungen an Philcoxia und Drosera zonaria wäre zu prüfen, ob auch bestimmte Pinguicula-Arten weitgehend von Quartzsand bedeckt wachsen, gedeihen und sich fortpflanzen könnten. Prediction: Auch wenn das der Fall sein sollte, werden sich nach dem Gesetz der rekurrenten Variation solche Pinguicula-Arten genausowenig wie Philcoxia und Drosera zonaria zu völlig neuen Formen der Karnivoren mit völlig anderen Fangstrategien entwickeln.

Anmerkung 2 ("highly specialized niche")

Pereira et al. (2012) heben hervor, dass die drei Philcoxia-Species nur in den “well lit and low-nutrient soils in the Brazilian Cerrado“ vorkommen – was jedoch auf eine ganze Reihe anderer Karnivorenarten nicht zutrifft (vgl. wieder http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ). Tatsächlich bildet Philcoxia in entscheidenden Punkten eine Ausnahme zu den übrigen Karnivoren (Pereira et al. p. 2):

On a global scale, the concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in carnivorous plant leaves tend to be lower than in leaves from noncarnivorous species (6). However, in their natural habitat, we found a higher nutrient concentration in P. minensis leaves compared to noncarnivorous neighbors, suggesting that carnivory contributes significantly to the mineral nutrition of this species. This is one of the few cases supporting one of the two energetic advantages of carnivory proposed by Givnish et al. (4) – that is, the elevation of photosynthetic rate through an increase in leaf nutrient content.

In weiteren Ausführungen zur hoch spezialisierten ökologischen Nische scheinen jedoch die Autoren dazu zu tendieren, notwendige mit hinreichenden Bedingungen zu verwechseln (p. 1):

Philcoxia comprises three species, all of which grow exclusively in the Campos Rupestres [rocky grasslands] of the Central Brazilian cerrado biome (9, 10), a species-rich mosaic of well lit and low-nutrient rock outcrops and shallow, white sands under a seasonal precipitation regime. According to the cost-benefit model, these conditions are conducive for the evolution of carnivory, and indeed species of the carnivorous genus Genlisea are common in this habitat where seepages [Sickerstellen] occur.

Man beachte, es handelt sich um ein "species-rich mosaic of well lit and low-nutrient rock outcrops and shallow, white sands under a seasonal precipitation regime". Alves et al. (2007) zur Speziesvielfalt des gesamten cerrado biomes 42 :

From the cerrado biome, Sano & Almeida (1998) report 6062 species (6389 taxa, including varieties) of flowering plants. Over 4000 of these species occur exclusively in the campos rupestres of the Espinhaço Range. Most of the cerrado species are adapted to periodical fires while several, known as pyrophytes, only complete their reproductive cycled when burned. 43

Wie hoch ist der Prozentsatz der karnivoren Pflanzenarten im Vergleich zu den nichtkarnivoren (auch hier)? Verschwindend gering, soweit ich bisher feststellen konnte (vgl. Fußnote 39). Würde man unter der Voraussetzung, dass die Bedingungen “conducive for the evolution of carnivory“ sind, nicht das genaue Gegenteil erwarten? Bestätigt das bisherige Ergebnis nicht die geringe Wahrscheinlichkeit der Bildung karnivorer Pflanzenarten durch Mutation und Selektion? Und nicht auch noch einmal die Richtigkeit von Karl von Goebels Wort: "Es geht so, aber es geht auch anders"? (Damit wird die selektionstheoretische Erklärung deutlich relativiert). Nur wenn in einer Spezies schon das genetische Potential für die Bildung synorganisiert-komplexer Fangstrukturen vorgezeichnet wäre und durch spezielle Umweltbedingungen nur ausgelöst (elicited) werden könnte, besteht eine hohe Wahrscheinlichkeit zur Bildung solcher Strukturen als aktives Anpassungsgeschehen. Dieser Ansatz impliziert Teleologie. (Vgl. http://www.weloennig.de/Gesetz_Rekurrente_Variation.html#cichlidae und dort zitiert mit Dawkins: "In der Evolution hat bisher nichts anderes als der kurzfristige Nutzen gezählt; der langfristige Nutzen war nie wichtig. Es ist nie möglich gewesen, dass sich etwas entwickelt hat, wenn es dem unmittelbaren, kurzfristigen Wohl des einzelnen Lebewesens abträglich gewesen wäre.")

Für intelligentes Design – "deliberate design by an intelligent agent" (Behe) – gibt es überdies auch die Möglichkeit der direkten Synthese völlig neuer Arten und Formen.

References

Alves, R. J. V. and J. Kolbek (1994): Plant Species endemism in savanna vegetation on table mountains (Campo Rupestre) in Brazil. Vegetatio 113: 125-139.

Alves, R. J. V., Cardin, L. and M. S. Kropf (2007): Angiosperm disjunction "Campos rupestres – restingas”: a re-evaluation. Acta Bot. Bras. 21: 675-685: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-33062007000300014

Dembski, W.A. and J. Witt (2010): Intelligent Design Uncensored. InterVarsity Press. Dovners Grove,Il.: http://books.google.de/books?id=qSUXHeCk9hwC&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq=Dembski+and+Witt&source=bl&ots=XIQ4nsnpMA&sig=tfF4prnrT2jKqY5pBY8fXWJXo5E&hl=de#v=onepage&q=Dembski%20and%20Witt&f=false

Fritsch, P. W., Almeda, F., Martins, A. B., Cruz, B. C. and D. Estes (2007): Rediscovery and Phylogenetic placement of Philcoxia minensis (Plantaginaceae 44 ), with a test of carnivory. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 58: 447-467.

http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/scipubs/pdfs/v58/proccas_v58_n21.pdf

Juang, T, C.-C., Juang, S. D.-C. and Z.-H. Liu (2011): Direct evidence of the symplastic pathway in the trap of the bladderwort Utricularia gibba L. Botanical Studies 52: 47-54. http://ejournal.sinica.edu.tw/bbas/content/2011/1/Bot521-06.pdf

Kitano, H. (2002): "Systems Biology: A Brief Overview," Science, Vol. 295:1662-64 (March 1, 2002). Zitiert nach C. Luskin: http://www.evolutionnews.org/2007/03/evolution_by_cooption_just_add003296.html

Kunze, R. Saedler, H. and W.-E. Lönnig (1997): Plant transposable elements. In. Classic Papers. Advances in Botanical Research 27:331-470. Co-option auf genetischer Ebene (pp. 425-429) auszugsweise (die Überlegungen zu den Duplikationen treffen auch ohne TEs [transposable elements] zu):

"(d) Gene duplications and TEs. To avoid the problem of "forbidden mutations" in the ultraconservative and conservative parts of the genome, where no or hardly any DNA-sequence changes can lead to deviating, yet vigorous phenotypes, and where most TE activities would probably be "selfish" in agreement with hypotheses 8-11, gene duplications with accompanying or subsequent base substitutions for putative new functions have proved to be the most often quoted alternative to the improvement of extant gene performances (see most textbooks on genetics). Interestingly, gene duplications, the production of redundant DNA sequences, by TEs have been reported by several authors (McClintock, 1951a, 1978; Birchler, 1994; see also Section VLB). Authors focusing on hypotheses 1-7, supposing that TEs may be important in evolution and generate the DNA sequence diversity needed for the origin of species, see in this fact further evidence for their views.

However, this is just the beginning of another research programme and not the full answer. Two basic problems have to be distinguished concerning the origin of new genes: the origin of new members of a gene family and the origin of the gene families themselves. From the evolutionary point of view there is no question that all the members of a gene family have to be explained by gene duplications and new families may be derived from sequences mutated beyond recognition of their relationships. It is, however, quite a different matter to induce gene duplications followed by sequence variations with selective advantages in the wild, and there is no experimental evidence to derive the thousand different gene families from each other. (Programmed gene amplification including gene conversion is a different topic.) […..]

(e) Goldschmidt's question on gene duplications. Richard Goldschmidt, a personal friend of Barbara McClintock holding cognate views of evolution (Lewin, 1983), raised some basic questions for gene duplications at a time when nothing was known about the idea of "junk" DNA. Goldschmidt (1955/1961) asked how a prospective new gene could be derived from a sequence of tightly linked successive steps of an already extant synthesis process in order to become a member of a perfectly new reaction chain also consisting of several co-ordinated new gene members (many again derived from genes of other chains present in the genome), which we have to assume, if an entirely new gene for completely new evolutionary steps arises.

Hence, some major problems have to be solved for gene duplications to be of fundamental evolutionary significance:

1. The "old" specific DNA sequence has to be transformed into a functional new one.

2. As in most cases one gene is not enough to create a new synthesis process (often dozens and more sequences are necessary), this new gene has to be integrated into the postulated new reaction chain.

3. The additional genes for the new reaction chain have to be recruited likewise from specific sequences and chains hitherto having quite different functions in an organism.

4. Addition and co-ordination of the new genes into a functional unit, consisting of about a dozen genes adequately expressed in space and time of developing organisms, resulting in selective advantages for the population possessing them will often also necessitate new regulatory gene functions, whose origin should also be contemplated.

5. What could be the selective advantages of the intermediate ("still unfinished") reaction chains?

The origin of glycolysis could be a paradigm for these questions (Fothergill-Gillmore, 1986; see also examples by Behe, 1996).

Let us have a closer look at what usually happens with a duplicate DNA sequence not under the constraint of organismal function and natural selection. According to Ohno (1970), the redundant locus is now free to store a series of forbidden mutations so that the polypeptide specified by it might eventually obtain a function considerably different from the original gene. "In such a way a series of new genes with previously non-existent functions must have emerged during evolution." Most textbooks of genetics have made similar statements from then onwards at the latest. However, the real scientific problems intrinsic in gene duplication for the creation of new genes are hardly disclosed in recent papers any more. Ohno came back to the subject of gene duplications in 1985. He mentions that a redundant copy is now free to accumulate random base substitutions, deletions and insertions, and that the most probable result is, not a new function, but degeneracy owing to the loss of promoter sequences, frameshifts, premature chain terminations, etc. Tens or even hundreds of duplicate copies will have joined the class of "junk" DNA for every new gene "that emerged triumphant". Finally, the author presumes that the existence of large numbers of pseudogenes reveals the inefficacy of gene duplication to generate new genes with new functions.

In 1970, Ohno spoke of gene duplications as a way a "series of new genes with previously non-existent functions" must have emerged, quoting several examples of related gene products. Fifteen years later, he explained the hypothesis in more modest terms, saying about redundant gene copies that "a few may emerge triumphant as new genes endowed with somewhat novel functions" (Ohno, 1985). Li (1980) commented that there is no general agreement on the question of how a new gene could arise from a redundant sequence. Some authors feel that the duplicate must soon come under the shelter of natural selection in order to avoid degeneracy, others argue that the redundant copy must pass through a period of silence to accumulate a sufficient number of mutations. Spofford (1972) found that the dissociation rate of duplicated genes is already much higher than the mutation rate by which genes with selective advantages could be formed. He therefore postulated monogenic heterosis as a refuge for the duplicates against the dissociation rate (see also Alberts et al., 1983). It may be emphasized again, however, that monogenic overdominance is a relatively rare phenomenon frequently connected with unusual environmental factors (for details, see Lönnig, 1993).

(f) Further questions on TEs and gene duplications. Clearly, for the topic of TEs, gene duplications and evolution, further scientific problems have not only to be investigated carefully but also need to be solved conclusively before sweeping statements concerning the origin of new genes from redundant copies mediated by TEs [or otherwise] are convincing. For instance:

1. What is the rate of gene duplications per gene per generation in different natural plant populations of various species owing to TEs in relation to other genetic factors as unequal crossing overs?

2. What is the rate of duplications subsequently being lost again owing to selective disadvantage (several such cases are known; Lönnig, 1993) or simply due to stochastic processes?

3. What is the ratio of duplicates becoming "junk" DNA lingering around for, perhaps, millions of years and never becoming functional again to those upheld with "somewhat novel functions"? (Ohno's "tens or even hundreds" of losses to one gain seems to be more an optimistic guess than the result of a detailed study — perhaps the number is only one gain to thousands or more losses.)

4. To what extent can "somewhat novel functions" be more clearly delineated? (Are they functionally comparable only to the pseudoalleles as Goldschmidt stated for duplications found in Drosophila or is there an experimental basis to believe that more can be expected?)

5. Are these ratios different for different genes and populations?

To work out further the details of the points enumerated some paragraphs before:

6. What is the probability of achieving entirely new DNA sequences and functions after gene duplications?

7. What is the likelihood of such new sequences becoming integrated into the extant co-adapted genome parts and functions?

8. What are the chances of obtaining entirely new reaction chains by gene duplications (see Goldschmidt's objections above) and, if there were any, could there be difficulties of integration again? (In transformed organisms we often find the phenomenon that the new gene (or genes), are silenced, for instance, by methylation; for details, see Meyer, 1995.)

Supporters of hypotheses 8-11 [selfish genes] could conclude that one cannot help but get the impression that, instead of solving basic evolutionary problems, there are intensifying improbabilities involved in the topic of TEs [or other factors] and gene duplications. Some mathematical calculations on both the origin of new functional gene members of a family as well as entirely new genes have shown several unsolved problems inherent in this subject (discussed by Schmidt, 1985; Wittlich, 1991; Lönnig, 1993). At present, it seems probable that TEs most frequently produce further "junk" DNA backing up the selfish TE hypotheses. Instead of generalizations from some more or less exceptional cases in cultivated plants under the shelter of human care and with no selective advantages in the wild, further research, especially with natural populations, is necessary to give realistic answers to these questions. [Anmerkung: Die Junk-DNA-Hypothese ist neuerdings stark relativiert worden, wenn auch ein Teil nach wie vor zutreffen dürfte: Vgl. z. B. Wells, J. (2011): The Myth of Junk DNA. Discovery Institute Press, Seattle. Siehe weiter Lönnig:

http://www.weloennig.de/RezensionKutschera.html unten zum Thema “DNA-Schrott” und Intelligent Design.

Menuge, A. (2004): Agents Under Fire: Materialism and the Rationality of Science. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Lanham.

Meyer, S. C., Minnich, S., Moneymaker, J., Nelson, P. A. and R. Seelke (2007): Explore Evolution. The Arguments For and Against Neo-Darwinism. Hill House Publishers, Melbourne and London.

Minnich, S. A. and S. C. Meyer (2004): Genetic analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic bacteria. Second International Conference on Design and Nature, Rhodes, Greece: http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/filesDB-download.php?id=389 (Design and Nature II. Comparing Design in Nature with Science and Engineering. Editors M. W. Collins and C. A. Brebbia, WITpress.)

Pereira, C. G. and R. S. Oliveira (2010): Philcoxia. Beitrag inMcPherson, S. (2010): Carnivorous Plants and their Habitats. Volume 2. Edited by Andreas Fleischmann and Alastair Robinson. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole, Dorset, England (pp. 1088-1103).

Pereira, C. G., Almenara, D. P., Winter, C. E. Fritsch, P. W., Lambers, H. and R. S. Oliveira (2012): Underground leaves of Philcoxia trap and digest nematodes. http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/01/04/1114199109.abstract

Porembski, S., Barthlott, W., Doerrstock, S. and N. Biedinger (1994): Vegetation of rock outcrops in Guinea: granite inselbergs, sandstone table mountains and ferricretes – remarks on species numbers and endemism. Flora 189: 315-326. (Bisher nur das Abstract gecheckt.)

Schäferhoff, B., Fleischmann, A., Fischer, E., Albach, D.C., Borsch, T., Heubl, G. and K. F. Müller (2010): Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 352 (pp. 1-22): http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352

Taylor, P., Harley, R. M., Souza, V. C. and A. M. Giulietti (2000): Philcoxia: A new genus of Scrophulariaceae 45 with three new species from eastern Brazil. Kew Bulletin 55: 155-163.

Zu den übrigen Literaturzitaten siehe: http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf

Die Quellen aus dem Internet wurden zwischen dem 20. und 30. Januar 2012 aufgerufen.

1Die Konvergenzen treffen wahrscheinlich auch auf die beiden anderen Arten der Gattung Philcoxia zu, nämlich P. bahiensis und P. goiasensis.

2"Truly carnivorous”: this has been confirmed and just been published by Pereira et al. 2012.

3 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352 (Schriftbild hier und im Folgenden von mir); siehe auch http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philcoxia (die drei Familien, in denen die Karnivorie innerhalb der Lamiales unabhängig entstanden ist, sind demnach die Lentibulariaceae (mit den Gattungen Pinguicula, Genlisea, Utricularia), die Byblidaceae (Byblis) und die Gratiolaceae (mit zahlreichen nichtkarnivoren Gattungen und der karnivoren Philcoxia). Zum Familienstatus der Gratioleae bemerken Schäferhoff et al. (2010): "Some genera from tribe Gratioleae, including Gratiola itself, have been found in a well supported clade. Based on the unknown relationships to the other lamialean families, it has been suggested to separate this part of the inflated Plantaginaceae by restoring family rank to former tribe Gratioleae from Scrophulariaceae as traditionally circumscribed (2)”; "Rahmanzadeh et al. [ 2 ] argued that the finding of a well supported clade including genera from Gratioleae together with unclear relationships of this group to other families is handled best with the recognition of a separate family. Thus, Gratiolaceae were resurrected.” "…Gratiolaceae is monophyletic and comprises the genera Achetaria, Bacopa, Conobea, Dopatrium, Gratiola, Hydrotriche, Mecardonia, Otacanthus, Philcoxia, Scoparia, Stemodia and Tetraulacium” ( http://www.academicoo.com/tese-dissertacao/phylogeny-of-lamiales-with-emphasis-on-gratiolaceae-species-to-brazil )

4Zum Teil nach Pereira et al. 2012.

5Zum Gebrauch des Begriffs "Neodarwinismus" vgl. zum Beispiel Hughes 2011 (17mal), Chevin und Beckerman 2011 (12mal) sowie Lönnig http://www.weloennig.de/BegriffNeodarwinismus.html

6 Konvergenz: "Unter Konvergenz […] versteht man in der Biologie die Entwicklung von ähnlichen Merkmalen bei nicht näher verwandten Arten, die im Laufe der Evolution durch Anpassung an eine ähnliche funktionale Anforderung und ähnliche Umweltbedingungen (ähnliche ökologische Nischen "Stellenäquivalenz") ausgebildet wurden. Damit wird impliziert, dass sich bei verschiedenen Lebewesen beobachtete Merkmale auch direkt auf ihre Funktion zurückführen lassen und nicht unbedingt einen Rückschluss auf nahe Verwandtschaft zwischen zwei Arten liefern" ( http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konvergenz_(Biologie) .

7 http://www.evolutionnews.org/2010/09/implications_of_genetic_conver037841.html

8 http://www.evolutionnews.org/2011/10/fact-checking_wikipedia_on_com051711.html (siehe die Fußnoten mit weiteren Hinweisen auch p. 7)

9 Siehe ausführlicher http://www.ideacenter.org/contentmgr/showdetails.php/id/1490

10Ähnlich Pereira et al. (2012, p. 1): "Carnivory has evolved at least six times within the angiosperms and […] approximately 20 carnivorous genera distributed among ten families and four major lineages have been identified (2, 3).”

11 Lönnig und Becker 2004, p. 5.

12 siehe weiter auch http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philcoxia

13 http://www.fr-online.de/natur/fleischfressende-pflanzen-philcoxia-jagt-mit-wurmfalle,5028038,11409850.html

14 Siehe dagegen Barry Rice, zitiert unten sowie die dazu wiedergegebene Abbildung.

15 "absenkt" ist falsch – vgl. die Details unten: die Blätter streben nach oben zur Bodenoberfläche.

16 http://www.dradio.de/dlf/sendungen/forschak/1649940/

17 http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/natur/0,1518,808094,00.html

18 Wie aber bekommt man ein "Gas" in die Fadenwürmer? Genauer: "NA22 Escherichia coli bacteria were grown in CGM-1020-SL-media (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) for 15N labeling. […] Nematodes of the species Caenorhabditis elegans were fed the isotope-labeled bacteria" – Pereira et al. 2012, p. 5.

19 http://www.wissenschaft.de/wissenschaft/news/314800.html

20Bei Fritsch et al. (2007) findet sich die genaue Taxonomic Treatment. Wie auch z. T. unter der Abbildung zitiert, beschreiben sie die Blattspreite u. a. wie folgt: "young laminae conduplicate; lamina subterranian or (when mature) at soil surface” – Fritsch et al. 2007, p. 453 (dort ausführliche weitere Beschreibung).

21 http://www.ideacenter.org/contentmgr/showdetails.php/id/1490 or http://www.evolutionnews.org/2010/09/convergent_genetic_evolution_s037781.html

22 http://www.evolutionnews.org/2011/01/common_design_in_bat_and_whale042291.html (echolocation: “...two new studies... show that bats' and whales' remarkable

ability and the high-frequency hearing it depends on are shared at a much deeper level than anyone would have anticipated - all the way down to the molecular level.”)

http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/27/17/3389.abstract (Ein weiteres völlig unerwartetes Beispiel!)

http://preventingtruthdecay.org/convergentevolution.shtml (Der an dieser Frage interessierte Leser findet hier eine ganze Serie weiterer Beispiele.)

23Nach Fleischmann und anderen haben Drosera und Drosophyllum jedoch einen gemeinsamen karnivoren Vorfahren.

24Wie oben schon erwähnt: zum Teil nach Pereira et al. 2012.

25 http://www.amazon.de/Die-Evolution-karnivoren-Pflanzen-Wasserschlauch/dp/3869914874/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1327171562&sr=1-2

26Vgl. Lönnig 2012, pp. 84-89, 98-100.

27 (Anwendung hier auf "the third independent origin of the syndrome within the order".)

28Details siehe http://www.weloennig.de/Loennig-Long-Version-of-Law-of-Recurrent-Variation.pdf

30Weiter könnten mutationsgenetische Studien mit Philcoxia durchgeführt werden, etwa saturation mutagenesis u.a. zum Nachweis von potentiell irreducibly complex structures or systems (Behe) und zum Studium des phänotypischen Divergenzpotentials samt Selektionswertuntersuchungen.

31 http://www.evolutionnews.org/2011/09/a_lost_attempt_to_critique_int050431.html

http://www.evolutionnews.org/2011/01/common_design_in_bat_and_whale042291.html

32 Vgl. z. B. Lönnig 2012, p. 118.

33 Oder direkt hier nachsehen (2005): http://www.arn.org/docs/positivecasefordesign.pdf und (2011) http://www.evolutionnews.org/2011/03/a_closer_look_at_one_scientist045311.html ; dort auch die Literaturangaben.

34 http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2148-10-352.pdf

35 Bezieht sich (wohl vor allem?) auf die "gelegentlich schlauchförmig ausgebildeten Blätter" von Pinguicula agnata und auf die vermeintlich "fast vollständig blasenförmigen eingerollten Blätter" von Pinguicula utricularioides (siehe weiter Lönnig 2010/2012 pp. 84, 86-90, 96, 108, 131, 223 unter http://www.weloennig.de/Utricularia2010.pdf ). Von schlauchförmigen Blättern bei Philcoxia ist mir jedoch bisher nichts bekannt..

38 Hier fehlt der Unterschied zwischen Besiedlungsdichte und Zahl der Arten.

39 Einige Hinweise auf zahlreiche Arten jedoch unter: http://www.insectscience.org/11.97/i1536-2442-11-97.pdf , http://www.jstor.org/pss/20046465 , http://botany.si.edu/projects/cpd/sa/sa20.htm , http://www.uefs.br/ppbio/cd/english/chapter9.htm

Alves, R. J. V., Cardin, L. and M. S. Kropf (2007): Angiosperm disjunction "Campos rupestres – restingas”: a re-evaluation. Acta Bot. Bras. 21: 675-685: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-33062007000300014

40 http://www.amazon.de/Die-Evolution-karnivoren-Pflanzen-Wasserschlauch/dp/3869914874/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1327171562&sr=1-2

41 Versuchsbeginn: Donnerstag 12. August 2010, Versuchsende Mittwoch 22. September 2010. Den (Pilot-) Versuch müsste man mit verschiedenen Pinguicula-Arten und unterschiedlichen Böden mit größeren Pflanzenzahlen erweitern. [Mit der eventuellen Beschränkung auf schlauchförmige Blätter könnte man kaum einen oder gar keinen Versuch machen, weil diese so selten sind (wohl nur Modifikationen); vgl. weiter Fußnote 35.]

42“Biom=Bioformation: Die gesamte Biozönose (Pflanzen, Tiere, Pilze, Mikroorganismen) einer Ökoregion oder Ökozone, erkennbar an der Pflanzenformation ihrer Klimaxvegetation . Der US-amerikanische Botaniker Frederic Edward Clements prägte Biom in einem Vortrag am 27. Dezember 1916. Zu jener Zeit benutzte er das Wort noch als kurzes Synonym zu biotic community (Biozönose). [2] In dieser Bedeutung wurde es 1932 zur Klassifikation von Biozönosen verwendet“ ( http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biom ). “Als Cerrado, Cerrados oder Campos cerrados bezeichnet man die Savannen Zentral- Brasiliens . Mit einer Fläche von zwei Millionen Quadratkilometern umfassen sie ein Gebiet von der Größe Alaskas. Die Bundesstaaten Goiás , Mato Grosso , Mato Grosso do Sul und Minas Gerais sind von Cerrados bedeckt, ebenso wie Teile von Maranhão , Paraná , Piauí und São Paulo “ ( http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerrado_(Brasilien) ).

43Zum Endemismus generell vgl. die folgenden beiden Kapitel der Artbegriffsarbeit: http://www.weloennig.de/AesV1.1.Dege.html und

http://www.weloennig.de/AesV1.1.Ipop.html . Interessant zu den Zahlen d. Pflanzenspezies wäre auch die Angabe der endemischen Gattungen u. Familien(?).

44 Besser (unter anderem um Verwechslungen zu vermeiden): Gratiolaceae

45 Vgl. das Zitat nach Schäferhoff et al., zitiert auf der Seite 10: statt Scrophulariaceae wieder Gratiolaceae.